Game AI: Breathing Life into Digital Denizens

The outlaw Arthur Morgan has waylaid a rich-looking man, who is sprawled on the grass. Morgan fires a warning shot in the air to assert his dominance. A moment later, a bird flops to the ground, felled by his bullet.

A gamer inadvertently fired this one-in-a-million shot in Red Dead Redemption 2 (RDR 2), and his clip of the scene went viral, with fans wondering if the bird’s death at the hands of RDR 2’s protagonist was a scripted event. It is unlikely to have been scripted, but is rather the result of the interplay between complex AI systems in RDR 2 (2018).

When attacked, the AI-driven NPC responds realistically, trying to fend off the player. In response, the player fires a warning shot. As a result, another AI-driven NPC – a hapless bird – meets an untimely demise while flying directly overhead. The bird’s flight path has not been scripted so that it gets shot down by the player, it is merely following its own routine because RDR 2 endows both human and animal NPCs with complex behaviours and schedules, and the bird’s death is just one of the outcomes when such complex AI systems intersect.

In this blog we will explore key aspects of game AI, and the development of seemingly intelligent behaviours in NPCs in various games and franchises. Game AI has evolved from the simple computer operated opponents in Pong and early arcade games to increasingly complex NPC agents in games such as RDR 2, the Halo franchise and Bethesda’s Elder Scrolls games. Developers have contributed significantly to defining, and redefining game AI, and games such as RDR 2 have pushed game AI to the limits, creating NPCs so convincing that they seem to have a life of their own.

What is Game AI?

Artificial intelligence in games – or game AI – is used to generate apparently intelligent and responsive behaviours mostly in non-player characters (NPCs, including human, humanoid and animal agents), allowing them to behave naturally in various game contexts, with human or humanoid characters even performing human-like actions.

AI has been integral to gaming from the arcade age – AI opponents became prominent during this period with the introduction of difficulty scaling, discernible enemy movement patterns and the triggering of in-game events based on the player’s input.

Game AI is distinct from the sort of AI we have become familiar with today, which is powered by machine learning and uses artificial neural networks. A key reason why in-game AI has remained distinct from today’s AI constructs is that game AI needs to be predictable to some degree. A deep learning AI can rapidly become unpredictable as it learns and evolves, whereas game AI should be controlled by algorithms that give the player a clear sense of how to interact with NPCs to achieve their in-game goals.

According to Tanya Short, game designer and co-founder of KitFox Games, game AI is to some extent “smoke and mirrors” – complex enough to make players think they are interacting with a responsive intelligence that is nevertheless controlled and predictable so that gameplay doesn’t go awry.

Within this relatively narrow scope, however, in-game AI can be quite complex, and game developers expertly fake the illusion of intelligence with various clever tricks – some developers have even experimented with giving more freedom to game AI, leading to interesting and unforeseen results.

What Types of AI are Used in Gaming?

Arcade games were the first to use stored patterns to direct enemy movements and advances in microprocessor technology allowed for more randomness and variability, as seen in the iconic Space Invaders (1978) game. Stored patterns for this game randomised alien movements, so that each new game had the potential to be different. In Pac-Man (1980), the ghosts’ distinct movement patterns made players think they had unique traits, and made them feel they were up against four distinct entities.

Over the years, certain key game AI techniques, such as pathfinding, finite state machines and behaviour trees have been crucial in making games more playable and NPC’s more responsive and intelligent. We delve into these below.

Pathfinding

A relatively simple problem for humans – getting from point A to B – can be quite challenging for AI-driven agents.

The answer to this problem is the pathfinding algorithm, which directs NPCs through the shortest and most efficient path between two parts of the game world. The game map itself is turned into a machine-readable scene graph with waypoints, the best route is calculated, and NPCs are set along this path.

Such an algorithm is particularly important and prevalent in real-time strategy (RTS) games, where player-controlled units need pathfinding to follow commands, and enemy-controlled units need the algorithm to respond to the player.

Early pathfinding algorithms used in games such as StarCraft (1998) ran into a problem – each single unit lined up and took the same path, slowing down the movement of the entire cohort. Many games then used various methods to solve this problem – Age of Empires (1997) simply turned the cohorts into an actual formation to navigate the best route, and StarCraft II (2010) used ‘flocking’ movement, or ‘swarming’, an algorithm devised by AI pioneer Craig Reynolds in 1986. Flocking simulates the movement of real-life groups such as flocks of birds, human crowds moving through a city, military units and even schools of fish in water bodies.

Finite State Machines

Finite state machines (FSM) are algorithms that determine how NPCs react to various player actions and environmental contexts. At its simplest a finite state machine defines various ‘states’ for the NPC AI to inhabit, based on in-game events. NPCs can transition from one state to another based on the context and act accordingly. If the NPC is designed to be hostile to the player character, seeing the player may lead it to run toward them and attack them. Defeating this NPC may impel it to run away, to go into a submissive mode, or simply enter the death state (i.e., die).

In fact, FSMs can ‘tell’ an NPC to ‘hunt’ players based on cues like audible or visible disturbances to the environment – this is a staple of stealth games, and the Metal Gear Solid franchise has used the hunting mechanic to create tense situations between the player and the NPC. Finite-state machines can also tell NPCs how to survive – under attack, they can take cover to improve health levels, reload ammunition or search for more weapons, and generally take action to evade death at the player’s hands.

Behaviour Trees

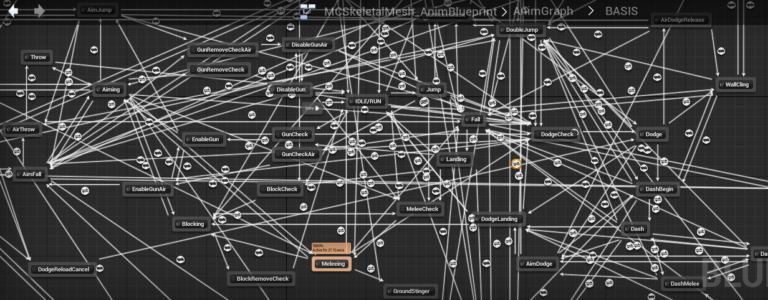

Unlike finite state machines, a behaviour tree controls the flow of decisions made by an AI agent rather than the states it inhabits. The tree comprises nodes arranged in a hierarchy. At the far ends of this hierarchy are ‘leaves’ that constitute commands that NPCs follow. Other nodes form the tree’s branches, which the AI selects and traverses based on the game context to give NPCs the best sequence of commands in any particular situation.

Behaviour trees can be extremely complex, with nodes attached to entire sub-trees that perform specific functions, and such nested trees enable the developer to create whole collections of actions that can be daisy-chained together to simulate very believable AI behaviour. As such, they are more powerful than finite state machines, which can become unmanageably complex as the number of possible states grows.

Behaviour trees are also easier to fine-tune and can often be altered using visual editors. You can even create behaviour trees in the Unreal Engine using a visual editor.

Notably used in the Halo franchise, behaviour trees have been part of developers’ AI toolkit for a while, and were used effectively in Alien: Isolation (2014). We will discuss their implementation both in Halo 2 and Alien: Isolation below.

How does Game AI Make NPCs Act Intelligently?

Various developers largely make use of the same fundamental concepts and techniques in creating game AI, but now employ them at much larger scales thanks to greater processing power. According to Julian Togelius, a New York University computer science professor, game AI is far more complex than the models discussed above, but are essentially variations on such core principles. In this section, we discuss some games that used AI inventively to create immersive encounters with responsive, intelligent NPCs.

Tactical Communications in F.E.A.R

First Encounter Assault Recon, or F.E.A.R (2006) created the illusion of tactical AI combatants using mainly finite state machines, with a twist – developers gave enemies combat dialogue that broadcast their strategy, which changed based on the game context. These ‘communications’ made players think they were up against situationally-aware enemies working together to defeat them.

The dialogue merely ‘verbalised’ the algorithms that directed NPC behaviour, but it added realism to enemy encounters – in real-life combat, soldiers do call out to their comrades to coordinate tactics, and in F.E.A.R, NPC soldiers would tell others to flank the player when possible, and even call for backup if the player was slaughtering them with ease. No real communication was taking place, but the NPC dialogue during combat gave the impression that the enemies were acting in concert.

F.E.A.R helped pioneer ‘lightweight AI’ and added nuance by giving voice to the AI’s ‘inner thoughts’. Snippets of combat dialogue beguiled players into thinking they were working against organised, tactical squads.

Halo 2: Aliens that Behave Sensibly

A key feature of the Halo franchise is the enemy – alien NPCs who have formed an alliance to defeat humankind. These visually unique NPCs give cues to the player about how to take them down. Grunts are small and awkward, and may flee from the player, but elites and larger NPCs may take on even the Master Chief in direct combat.

Rather than using finite state machines, Bungie used behaviour trees in Halo 2 to direct the actions of enemy aliens, because of the range of tactics made possible by sufficiently detailed behaviour trees.

At a very abstract level, Bungie’s behaviour trees have various conditional nodes that determine NPC actions. But a lot happens at any point in the game and the ‘conditions’ for many nodes may be satisfied, leading to game-breaking ‘dithering’, when an NPC rapidly alternates between various actions that are all deemed relevant. To prevent this, Bungie used ‘smart systems’ that enabled game AI to think in context.

Based on contextual cues (like the NPC type, its proximity to the Master Chief, whether it is on foot or in a vehicle), a system blocks off whole sections of the behaviour tree, restricting the NPC to a relatively small but relevant range of actions. Some of these remaining actions are prioritised over others, fostering sensible behaviour.

‘Stimulus behaviours’ then shift these priorities based on in-game triggers. If the Master Chief gets on a vehicle, then an enemy will seek a vehicle of its own, attempting to level the playing field for itself. Grunts will flee in the middle of combat if their captain is killed by the player – nodes that tell them to attack or take cover are simply overridden.

This can lead to repeated and predictable behaviour – the player might see the grunts fleeing and choose to target their captain the next time. But that strategy won’t work either: after a high-priority action such as fleeing is executed, a delay is injected to this behaviour to stop the NPC from repeating it immediately – the next time you take out the captain, the grunts may choose to stand their ground.

Bungie’s expert use of behaviour trees has led developers to adapt this game AI technique and it has since been used in several games, such as Bioshock Infinite (2013), Far Cry 4 (2014), Far Cry Primal (2016) and Alien: Isolation (2014).

Bethesda’s Radiant and Murderous NPCs

Halo’s enemy NPCs were essentially reacting to the player, but what if a developer wants to give the impression that NPCs are living lives of their own? Such an AI system would be especially useful in an open-world game, where a lot of NPCs may never engage in direct combat with the player, and exist to flesh out the world.

In Bethesda’s The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (2002), NPCs would pretty much ‘roam on rails’, lacking even the semblance of a routine. For The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006), Bethesda attempted to create complex NPCs with daily habits using Radiant AI, which had to be dumbed down considerably due to its unexpected in-game results.

In Oblivion, Radiant AI prescribes various daily tasks for the NPC, such as sleeping, eating and doing an in-game job. These tasks comprise the NPC’s daily routine, and the AI allows the NPC to decide how to perform its tasks.

Most games do feature NPCs with schedules, the key difference was the ‘free choice’ given to NPCs to do what they had to do in Oblivion. Playtesting revealed a rather big problem with this AI system – NPCs prone to murder.

As part of a certain quest, the player character needs to meet a dealer of Skooma – a highly-narcotic in-game potion. But the player would find this Skooma dealer dead because other NPCs designed to be ‘addicted’ to Skooma would simply kill the dealer to get to the drug, breaking the quest. In another case, a gardener could not find a rake, and so murdered another NPC, took his tools and went about raking leaves. When a hungry town guard left his post to hunt for food, other guards went along and the town’s malcontents started thieving indiscriminately as the law was nowhere in sight.

Many of these criminals had low ‘responsibility’, an in-game NPC attribute that determines how likely they are to behave in unlawful ways. An NPC with higher responsibility would buy food, but one with low responsibility might steal it – both are trying to fulfil the eating task, but are just going about it in radically different ways.

Of course, high-responsibility NPCs like guards won’t let crimes go unpunished, and an NPC who has stolen a loaf of bread can get killed. In the game, the player incurs a bounty if they commit a crime, and can pay instead of getting into a lethal encounter. This alternative was not granted to NPCs, so minor theft escalated to murder.

Designer Emil Pagliarulo had to take steps to tone down Radiant AI, so that NPCs wouldn’t slaughter each other to complete their daily tasks, and describes Oblivion’s original Radiant AI as a sentient version of the holodeck (the holodeck is a life simulator from the Star Trek franchise).

But even in the finished version of the game, one can exploit Radiant AI in interesting ways. Oblivion’s game world features poisoned apples. If the player places these apples in a public place, an NPC will likely eat them and die. This has no connection to any quest – it is just a simple player action with disastrous consequences for an NPC.

Even in Skyrim (2011), Bethesda’s fifth instalment in the Elder Scrolls franchise, the fine-tuned version of Radiant AI makes for lethal stand-offs between NPCs. In this video, NPCs fight to the death to claim certain valuable items dropped by the player, and in fact, they might do the same even if the items aren’t particularly valuable. This behaviour is driven by Bethesda’s Radiant Story system, which creates random quests based on certain parameters (like the quest giver, the guild they belong to, and other contexts) and also makes NPCs react dynamically to player actions.

NPCs will ask the player character if they can keep any item the player has dropped (or fight other NPCs to claim it). A guard may berate the player if he drops weapons, pointing out that someone could get hurt, and even fine the player if they disregard the guard’s warning. Completing a quest for an NPC makes them friendly towards you, and you can take their items instead of robbing them. In fact, friendly NPCs will also attend your wedding if you get married.

Meeting and Making Your Nemesis in the Mordor Games

The Nemesis System used in Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor (2014) and Shadow of War (2017) is perhaps the one AI system that practically ensures that every player will encounter different villains in every playthrough.

The developer Monolith Productions essentially created a dynamic ‘villain generator’ in which the player’s hostile encounters with an orc would result in changes to the orc’s status in the enemy hierarchy, his attitude towards the player, his powers, and more – if you set one on fire, he will hate you forever, and will develop a phobia for fire too, and if you run away from an orc in a fight, he will taunt you the next time you confront him. In effect, the Nemesis System turns a generic enemy into a named villain with unique traits.

The Nemesis System is largely made possible because Talion, the protagonist, cannot die, as he is in a state between life and death – lore is used to weave player death into the narrative and gameplay. This mechanic allows orcs and other enemies to remember Talion, hate him for what he has done to them, rise up the ranks by killing him and even gain a following because of their exploits – this can make them even harder to kill.

The Nemesis System is also built on the idea that the orcs in Sauron’s Army are a bunch of back-stabbing, infighting brutes, who rise to alpha dog status by challenging and killing orcs higher up the hierarchy – orcs can become named villains not only by facing off against you, but also by taking on their commanders.

One of the late game objectives is to sow discord in Sauron’s Army and dismantle it thereby, and the best way to achieve this is by recruiting low-level orcs using a special power. Such allies will spy for you, betray and supplant enemy leaders, and even join you in fights against powerful named villains. This is part of Nemesis too – orcs can rise up, but can also lose status if you beat them or if their bid for more power backfires. ‘Turning’ such a weakened orc – or recruiting him – allows you to thin your enemy’s ranks: the game discourages indiscriminate killing.

The ability to recruit orcs, even high-level ones such as captains and warchiefs, was expanded in Shadow of War to build up a veritable army of one’s own. Even the orcs in the game have complex relationships and are less prone to butchering each other – an orc you kill may have a friend who will hunt you down to avenge his brother-in-arms.

Warner Bros, the publisher of the Mordor games, chose to patent the Nemesis System, preventing other developers from building on Monolith’s achievements. If the patent had not been granted, developers could have used Nemesis, or developed a system based on it, to create true drama between the player and their enemy, whose personalities grow every time they face off against each other.

The Perfect Monster in Alien: Isolation

Alien: Isolation developer Creative Assembly faced an unprecedented challenge when designing the game – how could game AI be implemented to recreate the perfect killing machine, the xenomorph, from the Alien movies?

As Ian Holm’s character says in the first film, Alien (1979), the xenomorph is the “perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility… [It is] a survivor…unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

The AI for such an entity has to be near-perfect as well – the horror game’s immersion would have been utterly broken if some bug made the xenomorph run around in circles, or behave like one of Oblivion’s Skooma-addicted NPCs. Every interaction between the player and the xenomorph had to be scary, believable and unpredictable.

The developers adopted a design mantra called ‘psychopathic serendipity’, where the xenomorph somehow seems to be at the right place at the right time, and foils your plans even when you successfully hide from it. While you can’t kill it, it can kill you instantly.

Developers used a two-tiered AI system to foster these ‘serendipitous’ encounters: a director-AI always knows about your location and your actions, and periodically drops the alien-AI hints about where to look for you. But the alien-AI is never allowed to cheat, it can only work with the clues it’s given. You can always evade, hide or take it by surprise. This makes the game unpredictable, both for the alien and the player.

The alien-AI has an extremely complex behaviour tree system that determines the actions it takes, and some of its nodes are unlocked only after certain conditions are met, making the xenomorph exhibit unnerving traits that suggest that it is learning from your actions. Other behaviours are unlocked as you get better at the game, enabling the xenomorph to keep you on your toes.

A dynamic ‘menage gauge’ however, increases based on certain in-game contexts, estimating how tense the player is. When it reaches a certain threshold, the xenomorph will back off, giving the player some breathing space.

The alien’s pathfinding algorithm is also tweaked to make it look like it’s hunting, searching or even backtracking, suggesting that it’s revising strategies on the fly. Such behaviour is activated either by giving the xenomorph areas of interest to explore, or making it respond to loud noises made by the player. The intentionally sub-optimal pathfinder makes the xenomorph stop at all points of interest, ramping up the tension, making the player wonder what it is up to. However, the alien will never look in certain areas of the game, as doing so would shift the game balance unfairly in its favour. Throughout the game, the alien never spawns or teleports anywhere (except for two cutscenes), but can sneak around so well that players think it’s teleporting.

The AI in Alien: Isolation creates a macabre game of hide-and-seek with one of cinema’s most fearsome creatures, whose animal cunning keeps you guessing throughout the game.

Peak Game AI in Read Dead Redemption 2

It is difficult to capture the full complexity of the in-game AI in Rockstar’s Read Dead Redemption 2 (RDR 2), but like Alien: Isolation, the game represents a novel layering of multiple AI systems.

In this game, you can interact with every NPC in a variety of ways, and they will react and comment on what they notice about you, such as the blood stains on your shirt, how drunk you are, or your ‘Honor’ level, which gauges the good you have done, and also affects how the player character Arthur Morgan behaves.

NPCs may ridicule your choice of clothing, and keep their distance if you are dirty. They also have their own complex schedules, not just restricted to doing their jobs. They will start looking over their shoulder if you follow them along their routine and may flee if you persist. In Grand Theft Auto V (GTA V), attacking an NPC might trigger various reactions like fleeing or even a counter-attack. An NPC in RDR 2, however, may not immediately draw their gun, but try to address the situation with dialogue, allowing for more believable interplay between the player and the NPC.

During actual combat, NPCs will act intelligently – they will dive for cover, grip wounded areas and even try to take down Morgan with a melee weapon when possible. Enemies under fire will behave differently from calm ones who are not in the thick of combat. If you take refuge in a building, NPCs will cover all exits before a coordinated attack.

The sparse wild-west world of RDR 2 meant that each NPC had to be given a unique personality and mood states. Rockstar engaged 1,200 actors from the American Screen Actors Guild to flesh out the NPCs, each of whom had an 80-page script, and captured the actors’ demeanour and mannerisms over 2,200 days of mo-cap sessions.

Even the wilderness teems with 200 animal species that interact with each other and the player, and are found only in their natural habitats – the vast open world features multiple ecosystems and animals react realistically to creatures higher up the food chain. Herbivores will flee at the sight of wolves, wolves themselves will flee from a grizzly bear and a vulture will swoop down on an abandoned carcass.

Rockstar also overhauled the animation system to create more accurate human and animal mannerisms in the game world, generating fluid movements without stiff transitions. The animation overhaul allows NPCs to react to the nuances of your facial expressions, your posture and mannerisms, especially as they all change due to the dynamic nature of the game world. A well-rested, well-fed Arthur Morgan looks different from one who is half-starved and muddy after an all-night trek, and NPCs will note this.

Rockstar also completely recreated horse animations from scratch and even allowed the horse AI to decide how to move based on the player’s input. As a result, your horse is practically a supporting character in the game, and there’s a Youtube video devoted just to how Rockstar made the ‘ultimate video game horse’.

One day, a fan exploring the game found a mounted NPC wearing the exact same clothes as the player character. In other games, with less variety in outfits, this will happen often, but RDR 2’s numerous outfits make this situation unlikely – until you realise the number of complex NPCs who share the world with the player. By sheer coincidence, an NPC had managed to choose the same clothes as the player – it is unlikely that the NPC’s choice of clothing is scripted and meant to surprise the player.

Simply put, RDR 2’s AI is massively complex and will surprise players for years to come with its emergent gameplay.

Conclusion

We have seen how game AI can create complex interactions with NPCs who can act quite intelligently in context.

In RDR 2’s case, NPCs are so complex that one can sense they have their own, complex lives, which are not just centred around the player. We may also assume that Rockstar did not use neural networks to power their game AI – the implementation of state-of-the-art AI would have surely made it to promotional materials. Every game discussed above uses traditional techniques at greater and greater scales, and it is likely that game AI might eventually reach a plateau phase. What, then, is its future?

AI powered by machine learning and neural networks may soon become a viable means for playtesting. What if an AI such as this were allowed to play a million games of RDR 2 or Skyrim to fine-tune NPC behaviours, while still maintaining the balance of predictability and randomness game AI requires?

Most machine learning systems and neural networks work on vast datasets. Developers could perhaps take game AI to the next level by training a deep learning AI to amass and parse game AI behaviour, and improve it further still, and then create game AI – and new game AI techniques – for a subsequent game. Elder Scrolls VI, and Rockstar’s next open-world game, could perhaps benefit greatly from an AI created by AI.

Gameopedia offers extensive coverage of the AI used in all types of games. Contact us to gain actionable insights about how industry game AI techniques make games more believable and immersive.